Uttarkashi mayhem: In Dharali, the calendar is written in floods; here, clock ticks to the roar of Kheer Gad | Dehradun News

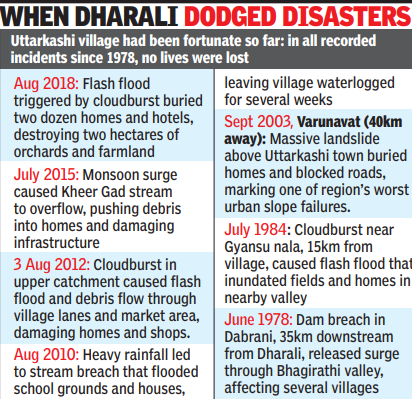

DEHRADUN: In Dharali, disaster isn’t the exception. It’s the architecture. And each time the Kheer Gad river roars to life, villagers climb to the roof and wait – not for rescue, but to see what’s left standing when the river leaves. The river doesn’t knock before entering the hamlet near Gangotri on the old Indo-Tibetan Silk route. It doesn’t announce itself with thunder or rain, just arrives – sudden, swollen, dragging centuries of stone behind it.In this village tucked into a crease of Uttarkashi, flood isn’t a headline. It’s a season in the calendar. Locals mark the years not by festivals or elections, but by the floods: the one in 2010 that soaked the school walls, the one in 2012 that swallowed a shop, another in 2018 that buried apple orchards under boulders taller than men. The Kheer Gad, a seemingly harmless trickle for most of the year, turns violent when cloudbursts hit Srikanth Parvat. And when it does, it doesn’t rise – it lunges.Despite the frequency and intensity of these disasters, Dharali had been extraordinarily fortunate so far: in all recorded incidents between 2010 and 2018, no lives were lost. The river took homes, orchards, roads, and livelihoods – but never a person.Also Read: ‘Bhaag bhai bhaag’: Multiple cloudbursts leave Uttarakhand people running for life – harrowing visualsDharali, with a population just over 500, sits along the Char Dham yatra route, 20km before the Gangotri shrine. In summer, its guesthouses and dhabas are packed with pilgrims and tourists, more than doubling the population; by mid-July, the rains begin and the village watches the stream. The 2018 flood – the worst before Tuesday’s – came in the early hours, leaving behind silence and the smell of wet iron. Nearly two dozen homes and hotels were reduced to rubble, two hectares of apple orchards disappeared under muck, and the road to the shrine was choked with silt and broken tin roofs.

Lokendra Bisht, an Uttarkashi resident, remembers 2018 clearly. “We dug out furniture from mud two days later,” he told TOI. “That time, no one died. But the loss – of homes, of work – it stayed with us longer than the flood.” He remembered 2012 the same way: quieter, but damaging. The Kheer Gad had risen again, this time pushing through homes and shops without warning.The pattern has grown hard to ignore. Over those years, the Kheer Gad behaved less like a stream and more like a fuse – short, volatile, and primed to detonate without warning. And each year, the debris has crept closer to the village centre. The stream begins on Srikanth Parvat and empties into the Bhagirathi river just downstream. The short run belies its power. When it floods, Dharali becomes a basin.Also Read: Uttarakhand cloudburst live updatesBefore the recent floods etched Dharali into disaster maps, destruction had already marked the valleys around it. In 1978, a dam breach near Dabrani, roughly 35km downstream, sent a rush of water through villages along the Bhagirathi. In 1984, a cloudburst over the Gyansu nala – just 15km from Dharali – triggered a flood that turned fields into silt flats overnight. And in 2003, a section of Varunavat mountain peeled off above Uttarkashi town, 40km away, burying homes and snapping roads. Dharali was spared each time, but the events traced a ring around it – as if the landscape had been circling the village, waiting.And the pushing hasn’t stopped. A 2013 report by the Uttarakhand Disaster Mitigation and Management Centre classified Dharali and nearby villages like Sukhi and Jhala as high-risk zones. The warnings were clear, but so were the incentives to ignore them. Hotels continued to rise on riverbeds. Pilgrim traffic swelled. Roads were widened. Slopes were cut. Experts who have studied the region’s topography have dire warnings. With glacial melt accelerating and rainfall patterns shifting, cloudbursts are now more frequent, and the consequences more immediate. “People think the mountain breaks in one night,” a geologist from the Wadia Institute once said. “But in reality, it’s been breaking slowly for years.”