The Niger uranium claim: How false documents fuelled America’s $1.7tn war in Iraq

In the months before the Iraq war, intelligence about Saddam Hussein’s weapons programmes moved through Western capitals with unusual urgency and little margin for doubt. Claims that Iraq was seeking uranium in Africa, a key ingredient for nuclear weapons, were treated as warning signs of an imminent threat. The implication was stark: a regime long accused of deception was once again edging towards the bomb.Yet the evidence underpinning this allegation was thin from the outset. It relied on a small set of documents alleging a uranium deal between Iraq and Niger papers that would later be exposed as forgeries and dismissed by nuclear inspectors and intelligence analysts alike.

Even before the invasion, doubts had surfaced inside the US intelligence community and among international watchdogs, raising questions about whether the case was being overstated or selectively framed.

How it all began

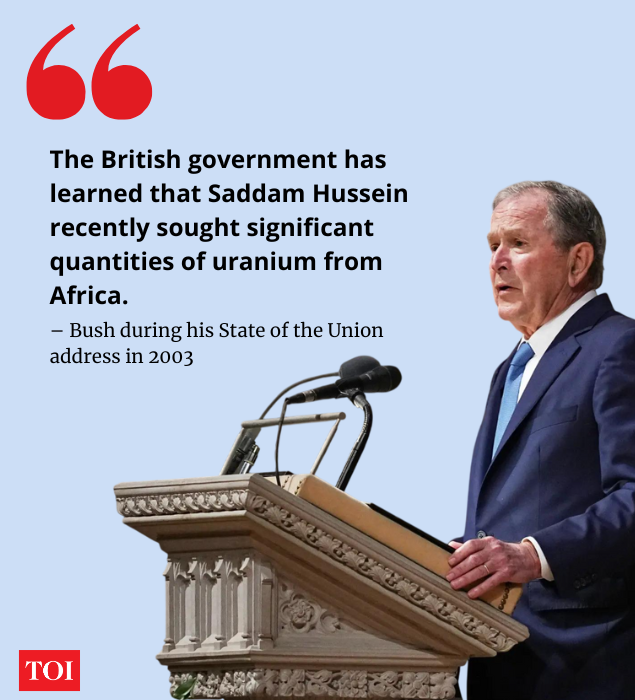

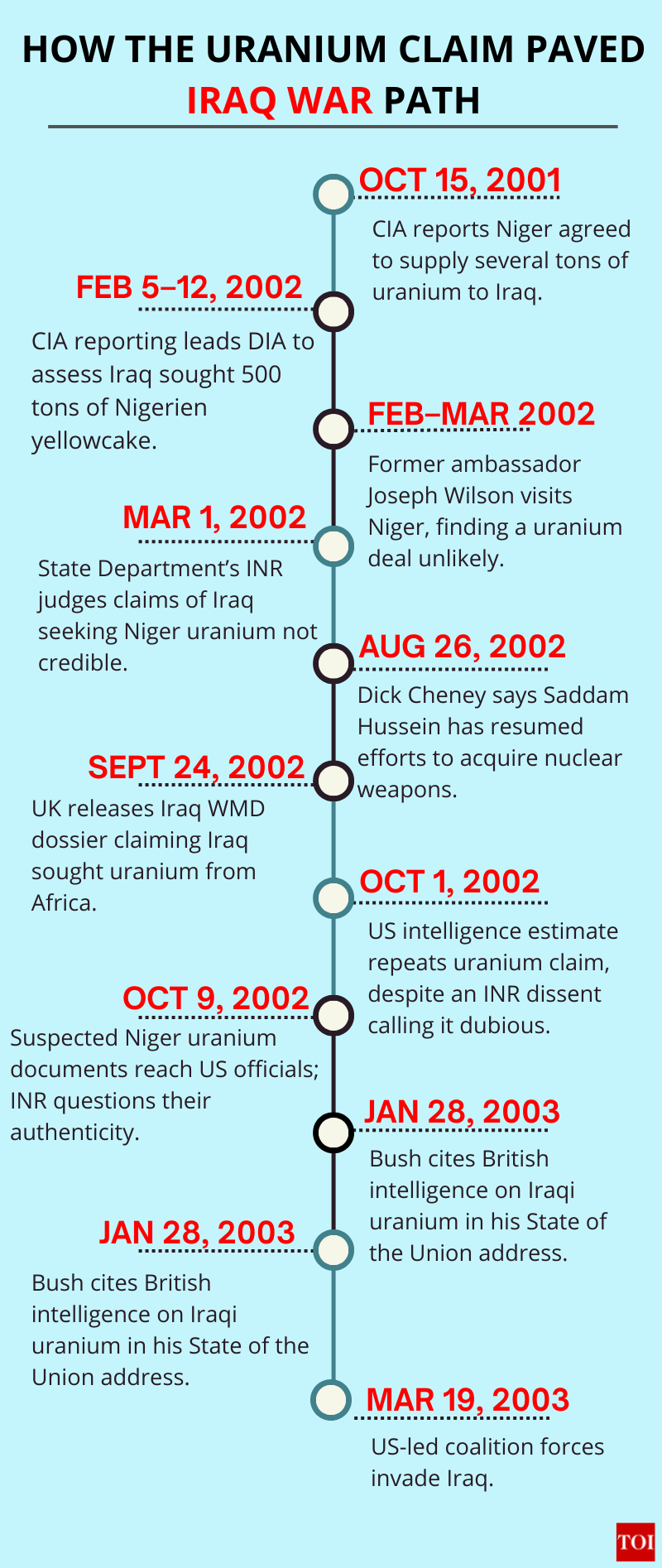

The story began with a set of documents in 2002 purporting to show that Niger, a uranium-rich West African state, had agreed to sell 500 tons of uranium ore (yellowcake) to Iraq. These “Niger letters” were circulated by Italian military intelligence (SISMI) and first surfaced in the Italian magazine Panorama. British and US intelligence soon received word of these claims. In a September 2002 British report on Iraqi weapons, the UK government stated there was intelligence that “Iraq has sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa”. In December 2002 and January 2003, top US officials, including National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, publicly repeated the allegation of an Iraqi hunt for African uranium. Finally, on January 28, 2003, President Bush declared in his State of the Union address that “the British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa”.

Those sixteen words became a cornerstone of the administration’s rhetoric on Iraq’s supposed nuclear threat.At the time, proponents argued the Brits had picked up credible leads about a covert Iraqi procurement effort. Britain’s dossier on Iraq was widely cited. Vice-President Dick Cheney warned in August 2002 that “Saddam has resumed his efforts to acquire nuclear weapons”, implying he was seeking fissile material like uranium. In his January speech, Bush treated the Niger claim as fact, implying that without an active reactor programme, Iraq had no legitimate reason for such uranium.

Intelligence scrutiny and dissent

Almost immediately, however, key elements of the Niger story came under scrutiny by US intelligence experts and other agencies. Soon after the Italian documents appeared in late 2002, analysts on the ground and at headquarters raised alarms. In October 2002, the CIA received the forged papers, but US Mission personnel flagged them as likely fake. When the State Department’s intelligence branch shared the documents with other agencies, it included a warning that their authenticity was “dubious”. By early 2003, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) had also examined the documents. Director-General Mohamed ElBaradei reported to the UN that the texts were “in fact not authentic” and that the uranium deal allegations were “unfounded”.Within the US intelligence community, scepticism was widespread. In a 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iraq’s WMD, a footnote from the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) labelled such claims “highly dubious.” The NIE itself warned that reports of Niger selling 500 tons of yellowcake could not be confirmed. Veteran CIA analysts in fact urged senior officials to drop references to an Africa-uranium plot.

Based on thorough analysis, the IAEA has concluded, with the concurrence of outside experts, that these documents, which formed the basis for the reports of recent uranium transactions between Iraq and Niger, are in fact not authentic. We have therefore concluded that these specific allegations are unfounded

IAEA Director-General Mohamed ElBaradei in March 2003

In October 2002, when preparing an earlier Bush speech, CIA Director George Tenet persuaded White House staff to remove a segment about Iraq seeking “substantial amounts of uranium” in Africa. In interviews before Congress, Tenet acknowledged only that there were “reports” of Iraqi attempts to buy uranium, not hard evidence. The picture that emerges is that intelligence agencies had mixed or negative assessments even as the administration used the allegation publicly.One key event was former ambassador Joseph Wilson’s February 2002 trip to Niger. Sent by the CIA to investigate, Wilson, who had previously worked extensively in Africa, interviewed local officials and reported back that the uranium story was baseless. The former Nigerien prime minister told him he knew of no sales to Iraq, and Wilson noted Niger’s uranium industry was tightly controlled and could not secretly ship off tons of yellowcake. Upon his return, Wilson told the CIA the entire affair was “bogus and unrealistic”.This intelligence was passed along within the Agency. Other senior American figures including Gen. Carlton Fulford, Deputy Commander of US Forces in Europe, who visited Niger, and Ambassador Barbro Owens-Kirkpatrick reached the same conclusion: the uranium deal was implausible given French oversight of Niger’s mines. By the time the administration made its formal case for war, however, Wilson’s negative findings had not altered the narrative.

‘Sixteen words’ and the state of the union

President Bush’s State of the Union address on 28 January 2003 crystallised the controversy. In a solemn tone about Iraq’s threats, he said:“The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.”This sentence consisting of exactly sixteen words, became one of the most scrutinised lines of the speech. The White House offered no footnote or explanation in real time, but critics immediately noted that no public evidence existed for the claim. In subsequent press conferences President Bush and his aides defended the assertion as reflecting allied intelligence. White House spokesmen insisted that it was based on British reports and other sources.It later emerged that some administration staff had serious reservations at the time. According to press reports, CIA Director Tenet and other analysts had specifically warned that the Niger evidence was single-sourced and uncorroborated. Deputy National Security Adviser Steve Hadley, in a summer 2003 briefing, disclosed that White House speechwriters had in fact removed an earlier draft reference to the uranium story from a Bush speech after Tenet and CIA experts objected. Yet by January 2003 the reference reappeared in shorthand form, citing only “the British government.” National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice later said she did not recall knowing of the October warnings when the State of the Union was drafted, claiming “we wouldn’t have put it in the speech if we had known what we know now”.Congressional investigators also examined the origins of the “sixteen words.” A US Senate Intelligence Committee report from July 2004 found that while British intelligence assessed Iraq had attempted to negotiate for Niger uranium, the CIA had been privately telling lawmakers that the claim was unverified. A British review, the 2004 Butler Report) ultimately concluded there had been credible indications, dating back to a 1999 Iraqi visit to Niger, that discussions over uranium might have occurred; nonetheless, even the Butler report admitted the overall evidence was “inconclusive”. As CIA Director Tenet publicly acknowledged on 11 July 2003: “These 16 words should never have been included in the text written for the President… This was a mistake.”

Aftermath of the claims

With the Niger claim included among other WMD accusations, the United States, joined by Britain and other allies invaded Iraq on March 20, 2003. The stated goal was to eliminate Saddam’s alleged nuclear, biological and chemical arsenal.

In the chaotic months that followed, however, no stockpiles of nuclear material or actual weapons of mass destruction were found. US forces did discover that Iraq had large already-sealed stores of yellowcake in its inventory, but these dated from the 1980s and were locked under IAEA supervision. The Niger paperwork was never substantiated in any way. International inspectors pointed out that even the purported deal of 500 tons would have been nearly impossible to conceal, since it was a sixth of Niger’s total annual uranium output.By mid-2003 the IAEA made public that the Niger documents were forgeries. On 7 March 2003, ElBaradei told the UN Security Council that the papers submitted by US authorities were “not authentic” and the allegation of a uranium deal was unfounded. A week later Secretary of State Colin Powell, presenting to the UN, avoided any mention of the African uranium claim. In April 2003 coalition troops found no evidence that Iraq had active nuclear or other WMD programmes. Iraq’s declared nuclear reactor and centrifuge projects had been dismantled in the 1990s.In July 2003 the White House conceded it had been wrong to include the Niger reference, and National Security Adviser Rice defended Bush by saying the president had not knowingly uttered false information. Vice-President Cheney and others continued to emphasize other threats, such as bioweapons, but the credibility of the WMD case had been severely damaged.

A 1.7 trillion dollar war

Whatever the debates over justification, the war and occupation of Iraq exacted a steep price. Tens of thousands of people died, and the financial toll was enormous. An official US figure is that about 4,500 American service members died in Iraq, with some 32,000 wounded. Britain lost around 179 soldiers, and hundreds more troops from coalition partners were killed. Civilian deaths in Iraq are harder to count: the Iraq Body Count project estimates at least 150,000200,000 Iraqi civilians died from violence during the war and occupation. A 2013 study by Brown University’s Costs of War project put the civilian death toll, including combatants, insurgents, and security forces, at roughly $176,000189,000. Monetary costs ran into the trillions of dollars. Just direct US government spending on the war has been estimated at $1.7 trillion, with an additional roughly $0.5 trillion more for veterans’ care. Once future obligations such as lifetime health and disability benefits are included, some analysts estimate the total cost at over $6 trillion in present value. These huge sums were borrowed (adding interest burdens) and have been argued to divert resources from other needs.Beyond dollars and deaths, the Iraq war had far-reaching consequences. It contributed to widespread instability in the region, a costly insurgency and sectarian conflict, and a prolonged US military presence in the Middle East. Perhaps most poignantly, no nuclear weapons or active WMD programmes were found to justify the invasion. The Niger uranium affair ultimately exposed not a single failure, but a chain of them. Dubious documents were allowed to circulate, warnings from intelligence professionals were discounted, and uncertainty was gradually transformed into political certainty. In that process, the safeguards meant to separate analysis from advocacy proved fragile under the pressure of a looming war.The invasion of Iraq went ahead based on a broader narrative of weapons of mass destruction that did not withstand scrutiny, leaving governments to quietly retract their most dramatic assertions after the fact.Two decades on, the lesson is a sobering one. Intelligence, by nature, is imperfect; policy built upon it must therefore be cautious, transparent and honest about its limits.