Studying ‘too much’ doesn’t help you learn better: Here’s why and tricks that work instead

Do you think repeating formulas or practising more is always better? Neuroscience strongly disagrees. Overlearning, or continuing to study well beyond mastery, can be comforting but reams of research reveals that its benefits are majorly short-lived and superficial. It is like securing the first chapter while burning the book in front of you — sacred but unchangeable. In other words, this may feel productive. However, there is mounting evidence to suggest that it frequently results in rigidity, diminishing returns and even interfering with brand-new learning.

What is overlearning exactly?

The practice of continuing to study or practise a skill after it has already been mastered is known as overlearning. Simply put, it means doing more than just “getting it right.” Many students actually do it: Even when they no longer make mistakes, they keep practising the information or skill. Overlearning is the practice of practicing beyond the point of initial mastery, usually done to improve performance reliability and retention. Examples of overlearning include:

- Solving the same math problem repeatedly even after you have already solved it correctly several times.

- Memorising a speech and continuing to recite it daily even though you already know it by heart.

- Practicing piano scales long after you can play them fluently without error.

Overlearning can be beneficial for tasks requiring automaticity under pressure (e.g., musicians, emergency responders, athletes) or when long-term retention must be ensured in a short period. However, it can be harmful and be a waste of time if the information could be retained more effectively through interleaving, spacing or retrieval practice. It may also reduce brain flexibility for learning new information, as claimed by several neuroscience studies and create false confidence without real-world adaptability.

The problem of overlearning

Overlearning has its limitations and meta-analyses by Applied Cognitive Psychology show that while this popular study habit boosts short-term recall, it does not sustain benefit over time. Strategies like self-testing and spacing create effort that deepens learning.

Overlearning feels smart but it could be killing your brain’s flexibility! (Image: Pexels)

A 2005 study titled The Effect of Overlearning on Long-Term Retention established that the over-learners recalled far more than the low learners at a one-week test but this difference decreased dramatically thereafter. Long-term retention was improved by distributed practice and unaffected by overlearning, the research found. After one or four weeks, college students solving math problems showed no benefit from overlearning (doing more problems). Spacing learning, on the other hand, led to significant long-term gains through distributed practice.New learning may be obscured: Overlearning hyper-stabilizes a skill. It helps students keep their mastery of the first task but creates trouble in learning a second, similar task right after. Researchers have noted that it temporarily reduces brain plasticity, making new learning more challenging.

Repeating won’t make you smarter: Ditch this outdated study habit now!

Motivation is reduced: Learning is very uneconomical if it exceeds a certain limit because over-learning requires more time and energy where the learning effect will decrease, leading to distraction, boredom and fatigue in addition to cognitive disadvantages. This means that more effort does not always result in better learning. In cognitive tasks, overlearning does not support long-term flexibility or retention, highlighting its limitations in practical learning applications.

Tips that actually work

Overlearning may initially provide confidence and security and it may feel productive but research demonstrates that it frequently fails to maintain learning, resists new learning and even demotivates. There are methods that are more efficient and effective.

- Distributed (spaced) practice – Revisiting formulas at intervals enhances long-term retention and even boosts grades significantly. The trick is to spread formula reviews for example, review today, then in two days, then a week later to avoid cramming and support durable learning.

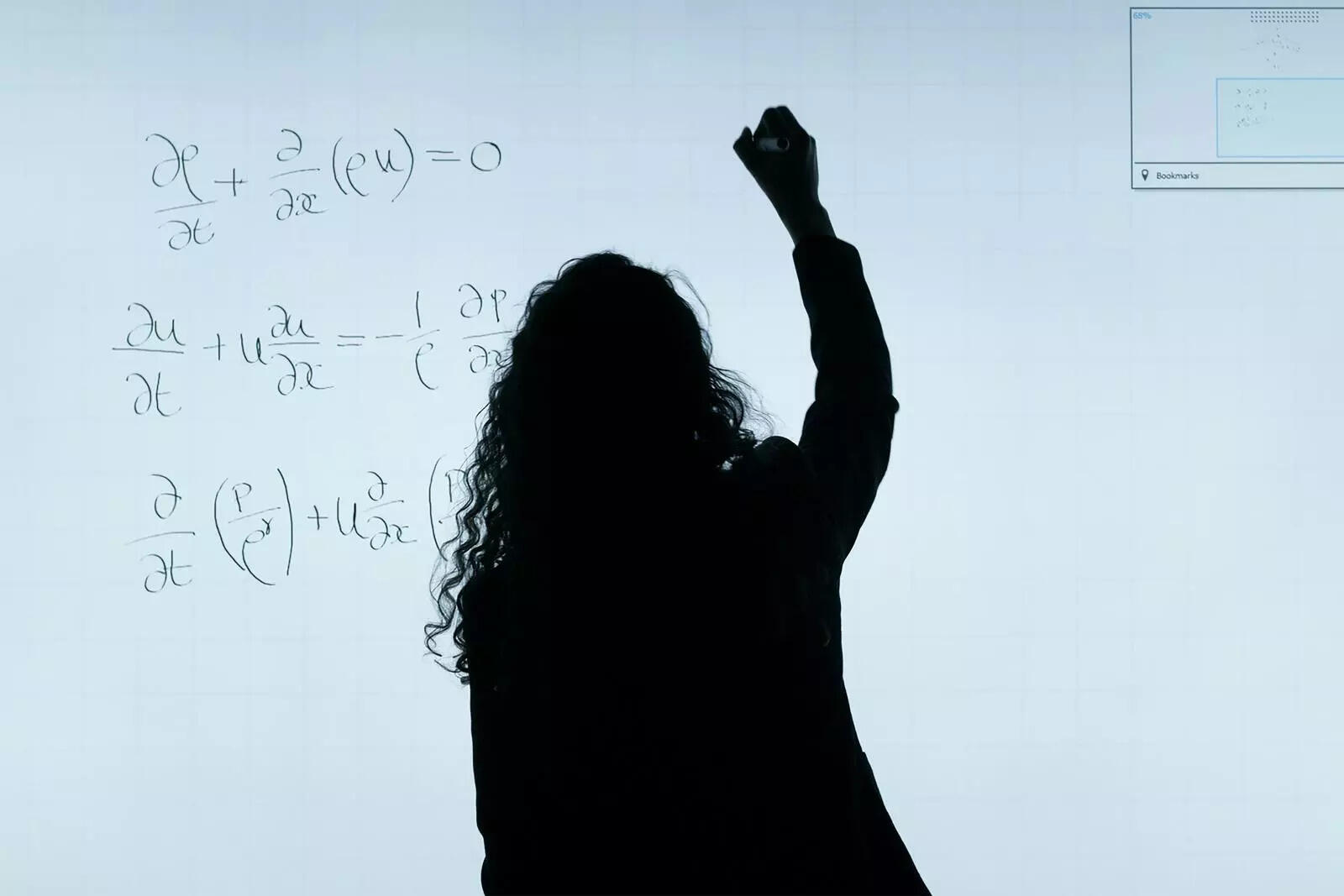

- Retrieval practice –

Rereading formulas is not nearly as effective as actively recalling them or so a study published inEducational Psychology Review, claims. The researchers found that through mechanisms like spreading activation and semantic elaboration, retrieval practice significantly improves long-term retention. According to a 2016 PubMed study, elementary-aged children (~10 years) showed strong retention gains through retrieval practice, regardless of reading or processing speed. So, quiz yourself instead of passively reading formulas by writing them down or practicing explaining their derivations. - Interleaved practice – Instead of blocking similar formulas, mix different types of formulas to make it easier to identify problems. This in turn makes them easier to use. Instead of practicing a single formula type repeatedly, alternate between multiple types like algebraic, geometry and calculus formulas to improve adaptability.

These methods promote flexibility, improve learning and help in long-term retention. Avoid mindless repetition and embrace challenging study. Instead of practicing too much in a single stretch, combine spacing with challenges.