Newton vs Leibniz: The calculus war classrooms never teach

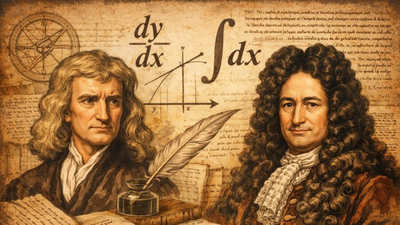

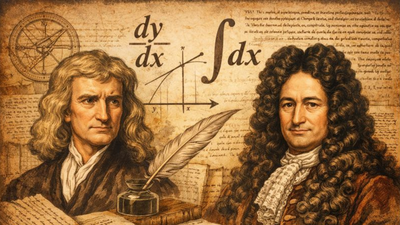

If you have read Neal Stephenson’s Quicksilver—the first volume of his Baroque Cycle (2003)—you will remember the smell of the age he recreates: Wet ink, gossip, gunpowder, and the new arrogance of reason. Science is not born in a laboratory alone; it is born in letters, salons, coffeehouses and committees, where ideas acquire patrons, enemies and, inevitably, owners. Stephenson makes this point early by dropping a very precise quarrel into the plot: Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz locked in a feud over who invented calculus—the mathematics that turned motion and change into something you could finally write down and claim. The quarrel Stephenson borrowed was not a literary embellishment. The Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy became a public fight from 1699, turned ferocious after 1708 and finally escalated into something like an institutional prosecution.

Newton’s unpublished calculus: Born in plague and paper

Newton’s calculus story began when Cambridge went quiet. During the plague disruptions of 1665–1667, he worked away from the university and shaped the ideas he later called fluxions—a way to treat change as something measurable, not merely observable. That “rates-of-change” instinct sat at the heart of calculus, but in Newton’s case it was born in private, not in print.The first major Newton text that mattered for the calculus trail was De Analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas (31st July, 1669). It looked, on the surface, like ‘infinite series’ rather than calculus—but it fed the same engine-room. Series methods were one of the 17th century’s most powerful ways to handle curves and difficult functions, and they helped turn calculus-style questions—areas, approximations, and the behaviour of changing quantities—into something computable. Newton wrote De Analysi as a manuscript and allowed it to circulate quietly. The world did not receive a clean publication timestamp in 1669, it received a set of working methods.By 1671, Newton had gone further and completed The Method of Fluxions—the explicit calculus text, the operating manual for his method of handling rates of change (fluxions). Yet, he did not publish it. His most famous public book, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), transformed mechanics, but it did not serve as a straightforward public claim to a teachable calculus in the way a journal paper did. Newton’s calculus remained, in effect, a private instrument.Only later did print begin to close the gap between Newton’s early work and the public record: De Analysi appeared in print in 1711 and The Method of Fluxions was finally published in 1736, posthumously. Calculus existed early, the timestamp had arrived late.

Leibniz put calculus into print first and that changed everything

Leibniz’s calculus story unfolded in the open. He moved through Europe as a mathematician-philosopher and political adviser, and treated knowledge as something that gained power only when it travelled. That instinct shaped the kind of calculus he built: Not merely a private method for solving problems, but a symbolic system that other minds could adopt quickly.By the 1670s, Leibniz had been developing the core ideas of his calculus and, crucially, its notation—the part that made it teachable. In 1675, he used the integral sign ∫ in his own notes, choosing a long “s” form because he conceived integration as a summing-up of infinitely many small parts. Then came the act that changed everything: Publication. In October 1684, Leibniz published Nova methodus… (short for a much longer Latin title) in the Leipzig journal Acta Eruditorum, a paper widely treated as the first public presentation of differential calculus. With that paper, calculus acquired a public timestamp. Leibniz did not stop after his 1684 paper. In June 1686, the same journal carried his next step in a paper placing the integral sign ∫ into print. That was the decisive contrast with Newton. Newton’s calculus had existed early, but it had lived largely in manuscripts and private circulation; Leibniz’s calculus had entered the public archive in 1684–1686 with a notation that travelled. Mathematics could coexist. The timestamps could not.

Who stole calculus?

Once calculus was in print, the story moved from mathematics into reputation-management. What followed was a battle for ownership and ownership invites accusations.In 1699, Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a Swiss mathematician in Newton’s orbit, publicly suggested that Leibniz had not merely arrived at similar ideas, but had borrowed them—an accusation that punctured the earlier, safer assumption of independent development. By 1708, the quarrel acquired a sharper public edge when John Keill, a Scottish mathematician and Newton partisan, accused Leibniz of having taken Newton’s method, specifically Newton’s unpublished fluxions work, and dressed it up as his own. Leibniz protested and took the matter to the one body whose judgement could bruise or bless a reputation across Europe: The Royal Society of London—an institution then led by Newton himself as its President. What followed in 1712–1713 looked less like scholarly disagreement and more like an institutional trial: A committee examined letters and manuscript trails, and the Society issued its report as the Commercium Epistolicum (published in 1713), arguing Newton’s priority.

Calculus: A method with two fathers

The honest conclusion, stripped of committee theatre and national pride, was almost disappointingly adult: Most historians treated calculus as an independent, near-simultaneous development by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz—Newton earlier in private, Leibniz earlier in print. Reference works described Leibniz as having independently developed differential and integral calculus; Newton’s biographies placed his early fluxional breakthroughs in the plague years, when Cambridge shut and solitude became a laboratory. Once you accepted that twin origin, the feud stopped looking like an argument about mathematics and started looking like an argument about modernity: an idea was not merely made; it was claimed. Newton held the earlier workshop and withheld the public timestamp. Leibniz printed the method, dated the pages—1684 and 1686 in Acta Eruditorum—and gave the world a notation that could travel faster than reputation.The subject carried its own irony. Calculus was the discipline built to handle continuity: to respect what cannot be pinned to a single instant, to describe change without demanding a drumbeat of absolutes. Yet its origin story became a stampede for absolutes—first, only, mine. Newton’s circle wanted manuscript priority to count as destiny; Leibniz’s circle wanted publication to count as birth. The dispute did what disputes always do when pride enters: it stopped asking what was true and started asking who would be believed. In the end, history delivered the only verdict that mattered, and it was not signed by any committee: the world kept Leibniz’s language, kept Newton’s physics, and forgot the bitterness whenever it needed an answer. Calculus survived because it was useful. The feud survived because it was human. And that, perhaps, is the final calculus lesson the classroom never teaches: Ideas converge, egos do not.