Explained: China’s population is not falling; it’s collapsing

China has had population control policies, which are now resulting in a declining population rate. To tackle that, it has now come up with some out-of-the-box ideas.From taxing condoms to proposing a dating course in the curriculum, the ideas seem bizarre. However, for a nation trying to cope with population decline after limiting families to just one, China is doing it all.

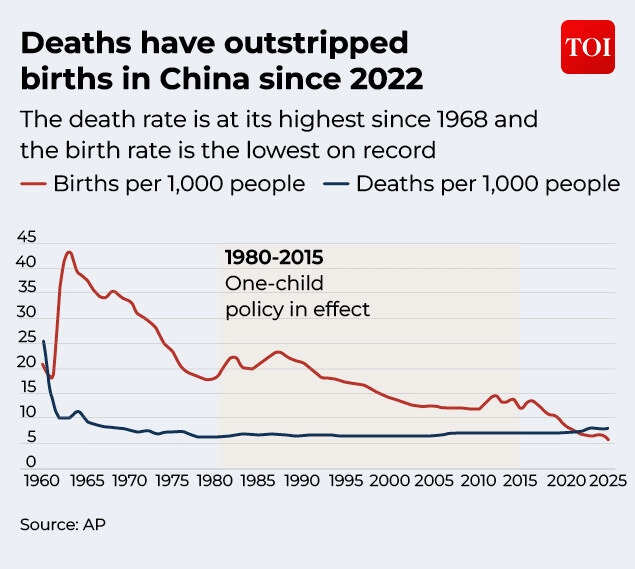

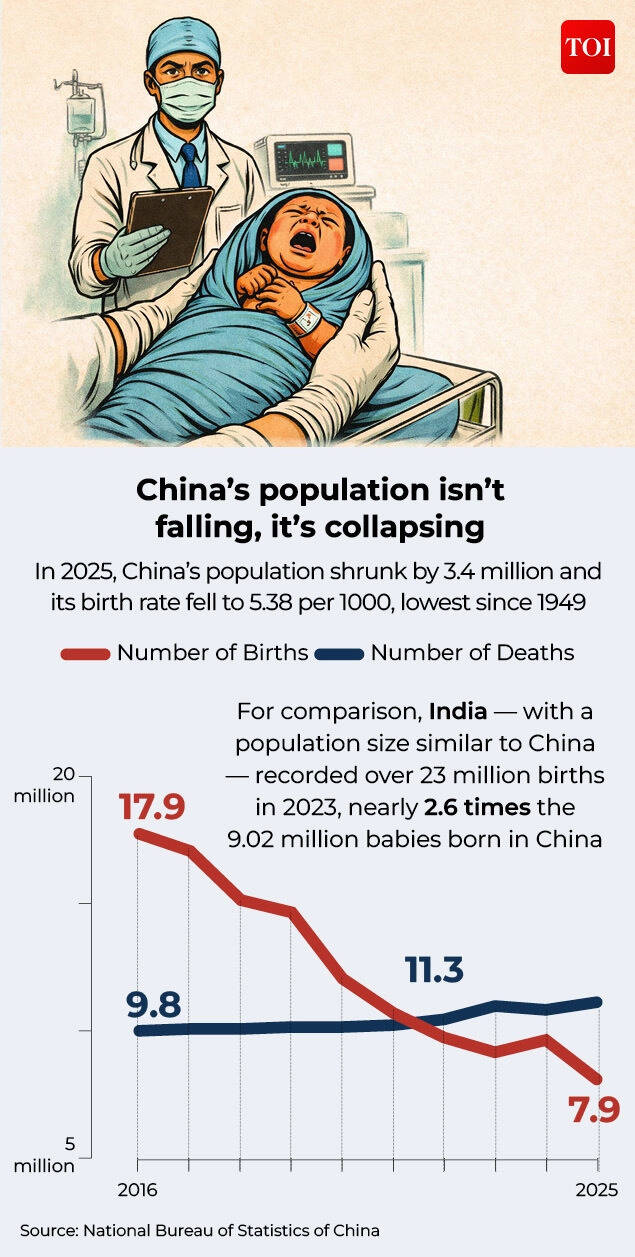

New government data released this week shows that China recorded its lowest birth rate since 1949 communist revolution, the year Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic. The country’s total population fell for the fourth straight year, dropping to 1.404 billion in 2025, about three million fewer than the year before, reports by news agency AP cited government data.The workforce is shrinking, pension bills are rising, and Beijing is scrambling to reverse a trend that it spent years embedding in the structure.

What the latest numbers show

China logged a birth rate of 5.63 per 1,000 people in 2025. The number of babies born that year was recorded as 7.92 million, which fell by 17% from 2024.2024 did reflect a small uptick in births, but it dipped sooner than policymakers could claim the credit for it.

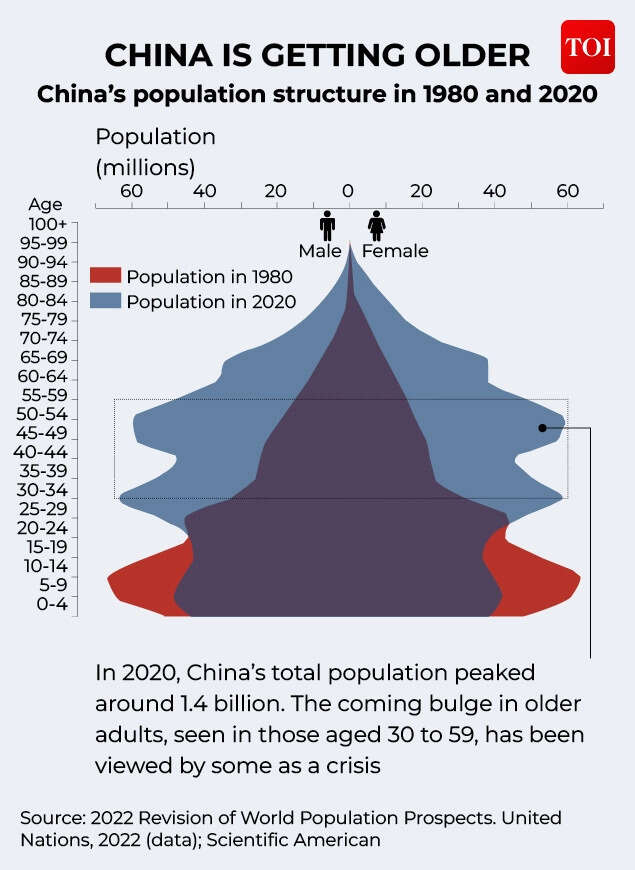

China’s fertility rate, or the average number of children a woman is expected to have, reinforces the picture. While Beijing last published an official fertility rate of 1.3 in 2020, independent estimates place it closer to 1 today, far below the 2.1 needed to maintain population size.For comparison, South Korea’s fertility rate is roughly 0.7, Japan’s is around 1.26, and the United States’ is roughly 1.6.The consequence? Retirees overpower the younger population.

How China went from controlling births to desperately promoting them

For centuries, population size was viewed as a strategic asset in China. Mao famously declared in 1957 that the nation’s 600 million people were its greatest strength, even as he warned about the difficulty of feeding them.But by the late 1970s, after years of famines and economic turmoil, Chinese leaders saw population growth as a threat to the country’s modernisation goals.

In 1980, four years after Mao’s death, Beijing introduced the one-child policy, a sweeping population control measure that limited most urban couples to one child. The policy remained at affect for 3.5 decades leaving deeper demographic marks:

- Gender imbalances from a cultural preference for sons

- Generations of “only children” with no siblings and fewer cousins

- Rapid ageing, as births slowed and life expectancy increased

- A shrinking workforce, particularly in urban centres

The policy then welcomed two children by 2015 and three children by the year 2021.

Why Chinese families aren’t having more children?

The end of the one-child policy didn’t spark a baby boom. Instead, it collided with a society that had grown more urban, educated and economically cautious.Several factors now weigh on prospective parents:

1. Economic Pressures

The cost of raising children in urban China from housing, education, healthcare to extracurriculars soared. With the economy slowing and youth unemployment high, many households simply feel they cannot afford multiple children.

2. Shifting Social Norms

Marriage rates are falling, and many young Chinese, especially women began opting to delay or skip marriage and childbirth. Work pressures, competitive schooling and long commutes leave little space for large families.

3. Lingering Policy Legacies

Families that grew up under the one-child policy internalised small-family norms. Parenting styles also shifted toward heavy investment in a single child, sometimes called the “little emperor” phenomenon.

4. Cultural Timing Factors

The Chinese zodiac bases its calendar by assigning an animal to each lunar year. In 2025, births were further tempered by the Year of the Snake, considered less auspicious for childbirth.

Beijing’s response: Subsidies, tax tweaks and social engineering

With young families reluctant to expand, the Chinese state has turned to financial and behavioural incentives.Recent measures include:

- Cash subsidies: e.g., 3,600 yuan (≈$500) per child in certain regions

- Tax changes: condoms are now taxed at 13% after losing VAT exemption

- Tax exemptions: for kindergartens, daycare centres, and matchmakers

- Propaganda campaigns: promoting “positive views” on marriage and childbearing

- Five-year plan targets: calling for reduced child-rearing costs and expanded support

China definitely walked the extra mile to make childbirth cheaper and instilling it in the social structure. But subsidies hardly compensate for the to real costs, and experts say the changes do not address structural challenges.

The economic consequences: Getting old before getting rich

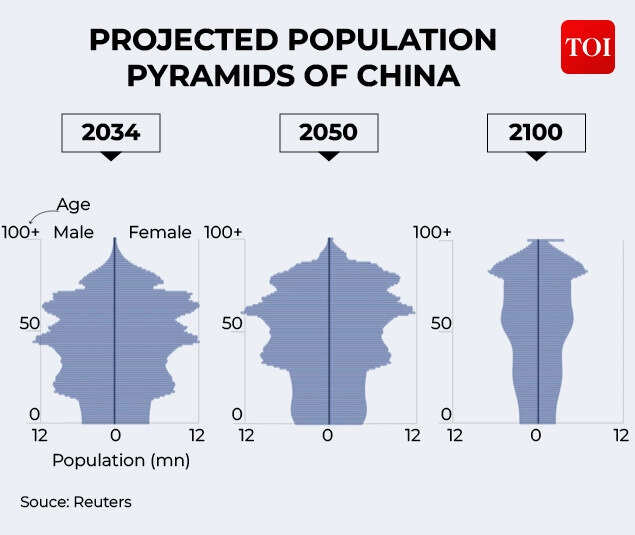

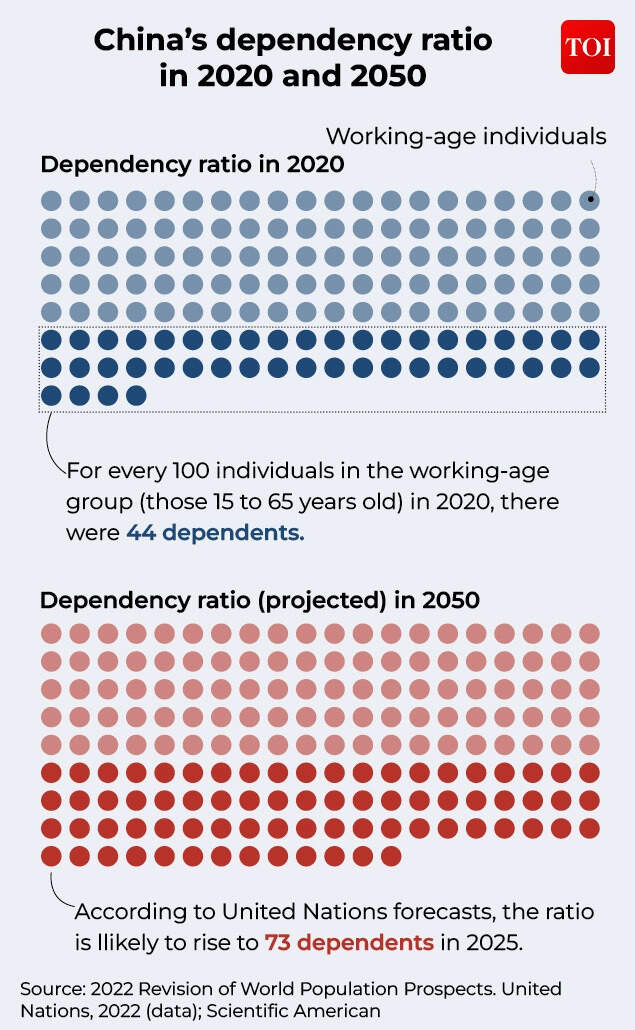

Why exactly is China pushing the population increase?Statistics show China is ageing fast. The country now has 323 million people aged over 60, about 23% of its population, and that share is rising.Economists warn that the workforce is shrinking while the number of dependents grows.

This shift raises several risks:

1. Slower Economic Growth

China reported 5 per cent annual economic growth in 2025. However, many analysts expect that to slow down. With tightening labour supply, productivity gains goes on to taper.

2. Pension and Healthcare Strains

More retirees mean pressure on state pensions and healthcare systems. Economists say China will eventually need to reform its pension system and broaden its tax base to cope with the higher government expenditure.

3. Industrial Transition Challenges

Beijing is trying to move from labour-intensive factories to high-tech manufacturing. But, in the consumer-driven economy, the high-tech automation cannot fully replace human workers in the short term.The worry is encapsulated in a phrase common among scholars: China is “getting old before it gets rich.”

Global implications: Demographics as strategy and status

Population size has long been a tool of Chinese statecraft. Under Xi Jinping, it is again framed as an element of national power. The nation built a “great wall of steel forged by over 1.4 billion people.”That framing has gained geopolitical relevance since India surpassed China in population in 2023. The two Asian rivals compete for leadership positions in the Global South, and demographic heft influences markets, diplomacy and military planning.

A shrinking population may not immediately diminish China’s influence, but it complicates long-term projections about innovation, consumption, and defence.

So what comes next?

China faces a demographic conundrum that has no easy fix. Similar problems have appeared in Japan and South Korea, but China’s scale makes the challenge unprecedented.Ultimately, reversing the decline depends on whether the state can:

- Make family life affordable

- Reform pensions and welfare

- Reduce pressures on working parents

- Encourage marriage and childbearing

- Sustain economic stability

But demographers warn that once fertility rates fall below a certain threshold, they rarely rebound. Amid the shift, aggressive state interventions pose next to no avail either.For a country whose leaders once tried to limit births at all costs, Beijing now finds itself asking a new and unexpected question: How do you persuade people to have more children in a society that has grown used to having fewer?