Archaeological evidence shows early Europeans celebrated war with brutality | World News

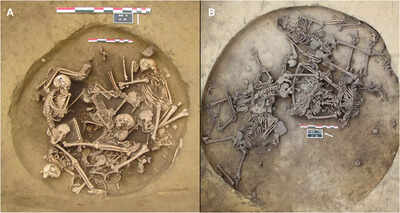

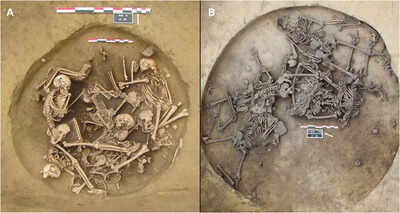

Burials uncovered in northeastern France have drawn renewed attention to evidence of organised violence in Neolithic Europe. Archaeologists studying human remains from pits at Achenheim and Bergheim, dated to roughly 4300 to 4150 BCE, report signs of extreme trauma and the deliberate severing of left arms. A new isotope analysis of 82 individuals, alongside animal bones and modern plant samples, suggests those killed were not local to the region. Chemical signatures preserved in teeth and bone indicate different diets and more mobile childhoods compared with people buried normally nearby. Researchers say the findings point to conflict between distinct groups during a period of cultural change in the Upper Rhine Valley, possibly marking one of the earliest documented examples of ritualised post conflict violence in prehistoric Europe.

Isotope testing reveals differences between victims and locals in war with brutality

The study, “Multi-isotope biographies and identities of victims of martial victory celebrations in Neolithic Europe”, compared individuals placed in irregular pits with others given standard burials. Stable carbon, nitrogen and sulfur isotopes were examined in bone collagen. Strontium and oxygen isotopes were measured in tooth enamel. Together, these markers help track diet, water sources and movement across landscapes.At both Achenheim and Bergheim, researchers found statistically significant differences between the two groups. Nitrogen values were notably higher among several of the victims at Bergheim, suggesting distinct food sources. Sulfur values also varied more widely among victims than among those buried in conventional graves.The differences were not uniform, which complicates the picture. Some individuals overlapped with local ranges. Others stood apart quite clearly.

Severed arms show separate chemical signatures

One detail stands out. Isolated left upper limbs recovered from the pits did not always match the isotope values of complete skeletons found alongside them. In several cases, the severed arms appear to have belonged to individuals with different dietary or environmental histories.This pattern has led researchers to consider the possibility of trophy taking. The limbs may not represent random mutilation. They could reflect a symbolic act following violent encounters. There is no written record to confirm this. The interpretation rests on bone chemistry and burial context.

Childhood mobility appears higher among victims

Teeth preserve early life information. By sampling dentine layers formed in infancy and childhood, the team traced changes in diet and landscape use over time.Victims showed more frequent chemical shifts during early years. Strontium ratios between first and second molars were greater on average than those of nonvictims. This suggests movement across different geological zones while young. Regional strontium variation remains wide, so none of the individuals can be labelled clearly foreign. Even so, the pattern of change differs.

Evidence aligns with broader Neolithic conflict

The sites date to a period of transition in the Upper Rhine Valley, when cultural traditions linked to the Paris Basin replaced earlier local groups. Fortified settlements and skeletal trauma from the era have been noted before.The pits at Achenheim and Bergheim add detail rather than drama. The evidence does not describe a single massacre in isolation. It hints at confrontation between communities, perhaps repeated over time. Bones, soil and chemistry offer fragments. They do not tell a full story. But they suggest that violence here was organised, deliberate, and remembered in ways that went beyond burial.