‘Khejri Bachao Andolan’: Why Rajasthan is rallying to protect its ‘Kalpavriksha’? Explained | India News

In the heat of Rajasthan’s desert districts, a tree has become the focal point of a widening confrontation. Markets have shut, saints have gone on strike, political rivals have shared protest stages, and thousands have gathered under open skies to demand its protection.What began in Bikaner as a local objection to the alleged felling of khejri trees for solar power projects has since evolved into the ‘Khejri Bachao Andolan’, a statewide campaign pressing for stricter legal safeguards and an immediate ban on cutting the species. The movement has drawn support across party lines, producing a rare moment of political convergence.The khejri, botanically known as Prosopis cineraria and recognised as Rajasthan’s state tree, occupies a distinctive place in the ecology of the Thar desert. Amid the ongoing protests, chief minister Bhajan Lal Sharma, assuring the protection of the khejri, termed the tree as the state’s “Kalpavriksha,” a wish-fulfilling tree in Indian tradition. In an arid landscape where survival is closely tied to ecology, the reference reaffirms the tree’s symbolic and practical importance. For many communities in western Rajasthan, the debate now extends beyond development policy into questions of history, identity and survival.

Protestors carried posters featuring a revered proverb in the Bishnoi community: “Sir saanthe rukh rahe to bhi sasto jaan” (If a tree can be saved, even at the cost of one’s head, consider it a bargain). (PTI)

How the agitation unfolded

The present phase of the movement intensified in early February, when over 360 saints and local residents began a hunger strike in Bikaner, demanding an immediate ban on the felling of khejri trees for solar power projects. The protest site was initially the Polytechnic College ground near the Collectorate before shifting to the Bishnoi Dharamshala, where the hunger strike continues.In Bikaner, markets remained closed for hours on Monday after a call by trader associations. Government and private schools in urban areas observed a half-day holiday in solidarity. Thousands gathered at the Polytechnic College ground before marching towards the Collectorate, where organisers announced an indefinite sit-in.Protesters came not only from different districts of Rajasthan but also from Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. Organisers said they had arranged food for nearly one lakh participants, with hundreds of volunteers handling logistics. Police deployed additional forces, erected barricades near the Collectorate and kept water cannons on standby. Despite the scale and tensions, the protest remained peaceful.

Environmental activists and members of the Bishnoi community participate in the Save Khejri Movement at Polytechnic College, protesting against the proposed cutting of Khejri trees for a solar power plant, in Bikaner. (PTI)

Four protesters were admitted to Prince Bijay Singh Memorial Hospital as their health deteriorated during the hunger strike, while several others received medical assistance at camps set up near the site. Mokhram Dharaniya, one of the hospitalised protesters, said, “People are sitting on a hunger strike, including me. Our protest will continue until our demands are met.”

The trigger? Solar expansion

At the centre of the agitation are allegations that large numbers of khejri trees have been cut to facilitate solar power projects in western Rajasthan. The region has emerged as a hub for renewable energy, given its high solar irradiance and availability of land. While solar development is central to India’s energy transition goals, protesters argue that project implementation has come at the cost of ecologically vital trees.Tensions escalated when the state government announced a restriction on felling khejri trees only in the Jodhpur and Bikaner divisions. Protesters rejected the move as inadequate, demanding a blanket statewide ban. During one address by a government representative, protesters reportedly took away the microphone, insisting on a written assurance.

Environmental activists and members of the Bishnoi community take part in the ‘Save Khejri Movement’, protesting against the proposed cutting of Khejri trees for a solar power plant, in Bikaner. (PTI Photo)

Minister for skill, employment and entrepreneurship KK Bishnoi and State Animal Welfare Board chairman Jaswant Bishnoi visited the Bishnoi Dharamshala and offered juice to the hunger strikers in an attempt to persuade them to break their fast. The minister said the government was ready to provide a written commitment and appealed to protesters to end the hunger strike. However, saints on the stage refused to withdraw without formal documentation.Agitation leader Parsaram Bishnoi said, “The hunger strike did not end. The government order was incomplete as it failed to cover the entire state.” Former minister Bhanwar Singh Bhati said: “All sections of society participating in the agitation decided to continue until a complete ban on cutting Khejri trees was imposed across Rajasthan.”

Storm in the assembly

The issue has resonated in the Rajasthan Assembly. Congress MLA Dungar Ram Gedar raised the matter during Zero Hour, accusing the government of failing to act despite a persistent two-year protest led by the Bishnoi community in Bikaner. “Khejri being the state tree, there is an urgent need for a strict law to protect it,” Gedar said.Independent MLA Ravindra Singh Bhati stated that the matter was already under discussion in the assembly. “Bhagat Singh (the Indian freedom fighter) said that sometimes a blast is needed to make the voice heard. If it takes gheraoing the Assembly to save khejri, I will be at the forefront,” he said.Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma told the assembly that his government was drafting a conservation law for the khejri tree, which he described as the state’s “Kalpavriksha”. “In August, saints from Bikaner, Phalodi, Jodhpur and Nagaur met me. Following that, I instructed officials to prepare the draft legislation. The process is under way, and it will soon be presented in the assembly,” he said.The chief minister also used the assembly session to defend his government’s broader record, speaking about economic growth, recruitment reforms and water supply projects. However, protesters have maintained that until a formal statewide ban is issued, the agitation will continue.Former chief minister and senior Congress leader Ashok Gehlot expressed support for the public movement, describing the indiscriminate cutting of khejri trees in the name of development as “extremely painful and unacceptable.” He recalled the historical sacrifice associated with the tree and said environmental protection must be prioritised.In a development seen as politically significant, former chief minister Vasundhara Raje publicly backed the movement that has put her own party, the BJP, in the dock.Sharing a photograph of herself worshipping a khejri tree, she wrote, “I also worship the Khejri tree. Rising above politics, we should all come forward to protect it. We must save it. I stand with everyone in the campaign to save the Khejri tree and the Oran (grazing land).” She also quoted a proverb revered in the Bishnoi community: “Sir saanthe rukh rahe to bhi sasto jaan” (If a tree can be saved, even at the cost of one’s head, consider it a bargain).Observers have noted that her intervention has added to political pressure on the state government.

Vasundhara Raje shared a photo of herself performing a ritual puja, while pledging cross-party support to protect these trees and associated Oran grazing lands from development threats.

The historical memory: Khejarli and Amrita Devi

Any discussion of the khejri in Rajasthan inevitably returns to the events of 1730 in the village of Khejarli near Jodhpur. According to historical accounts, 363 members of the Bishnoi community, led by Amrita Devi Bishnoi, sacrificed their lives to prevent the felling of khejri trees ordered for royal construction.The episode, often referred to as the Khejarli massacre, is widely regarded as one of the earliest recorded instances of environmental resistance. Amrita Devi is said to have declared that the loss of her head would be a small price to save a tree. Her sacrifice and that of the others form a cornerstone of Bishnoi identity and environmental ethics in the region.

According to historical accounts, 363 members of the Bishnoi community, led by Amrita Devi Bishnoi, sacrificed their lives to prevent the felling of khejri trees ordered for royal construction.

Protesters in the current agitation have repeatedly invoked this legacy. Even Ashok Gehlot referred to the sacrifice of 363 individuals, including Amrita Devi Bishnoi, and said their legacy should be honoured.

Ecological significance

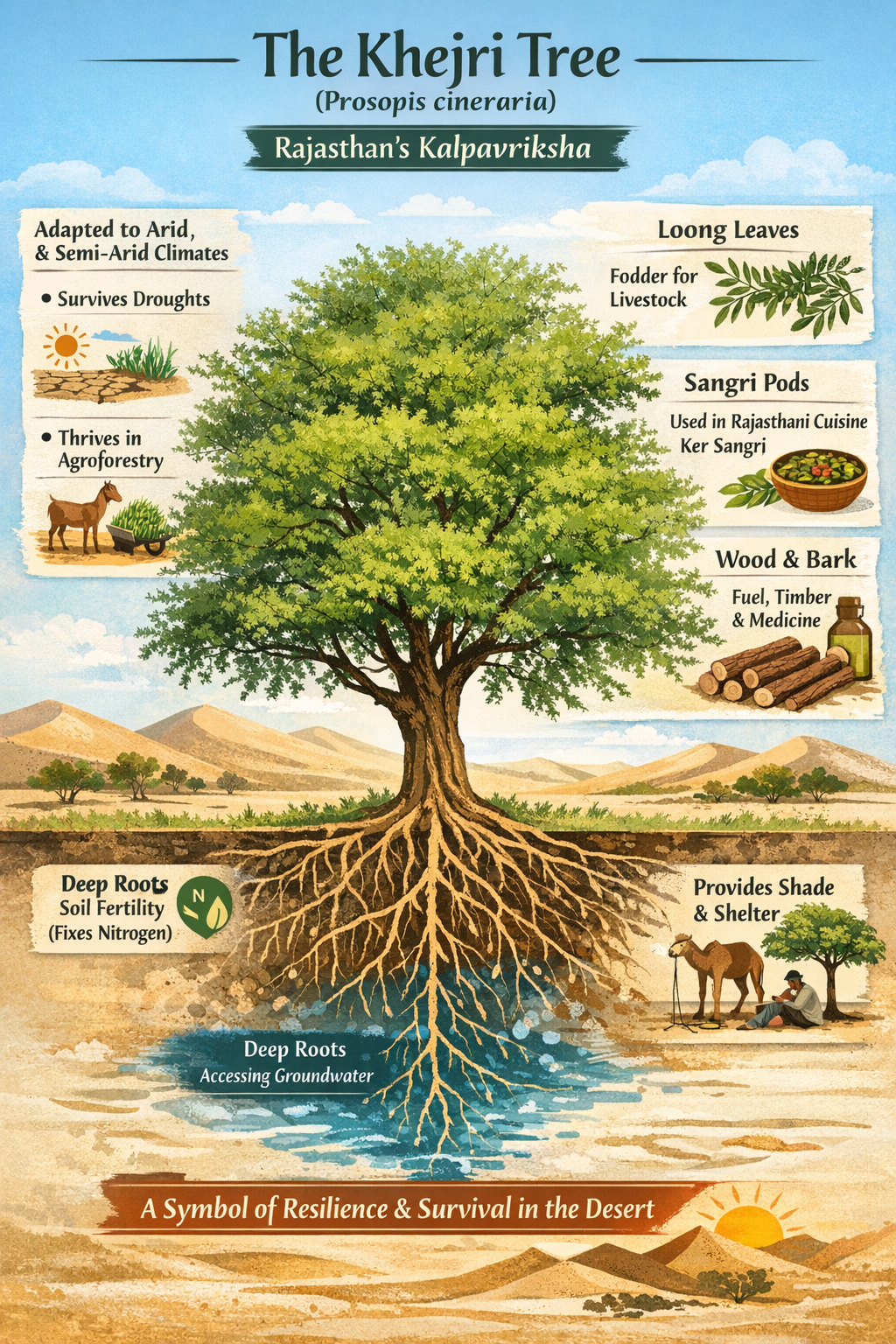

The khejri is uniquely adapted to arid (extremely dry) and semi-arid climates. It has a deep root system that allows it to access groundwater and survive prolonged drought. Unlike many other species, it does not compete aggressively with crops and is often grown in agricultural fields in a traditional agroforestry system. An agroforestry system is a land-use practice where trees are grown alongside crops or livestock on the same land to improve productivity and sustainability.Its leaves, known as “loong,” are used as fodder for livestock. Its pods, called “sangri,” are a staple ingredient in traditional Rajasthani cuisine, particularly in the dish Ker Sangri. The wood is used as fuel and timber, while its bark and other parts have been used in traditional medicine.

The Khejri tree (Generative image)

Ecologically, the tree improves soil fertility by fixing nitrogen, reduces desertification by stabilising sand dunes and provides shade in extreme heat. In regions where annual rainfall is minimal, it plays a crucial role in sustaining both human and animal life.Given these attributes, many in Rajasthan see the khejri not just as a tree but as a symbol of resilience and survival in a harsh environment.

Legal framework and demands

Currently, khejri trees are protected under various forest and environmental regulations, but protesters argue that enforcement is inconsistent and that ambiguities in existing laws create loopholes. Former Luni MLA Mahendra Vishnoi said, “Confusion exists in current laws concerning khejri conservation. The penalties must be precise and severe. Without a fear of the law, this destruction will persist.”Environmental activist Mokhram Dharniya alleged administrative inaction. “The administration has betrayed us repeatedly. Over the past year, we have held numerous protests, receiving assurances each time, while the trees continue to be axed. We will not permit the cutting of khejri anymore,” he said.One of the demands emerging from the agitation is a provision imposing a fine of Rs 1 lakh for violations. Activists have also called for a temporary statewide ban on felling until a comprehensive conservation law is enacted.

Spread of the movement

The agitation has extended beyond Bikaner. In Barmer, protesters gathered at the Collectorate, and some youths climbed the gate and raised slogans after police closed the premises. A memorandum addressed to the chief minister was submitted.The movement has also taken on a deeply personal dimension for some families. Following the death of environmental activist Radheshyam Bishnoi in a road accident last year, his mother Ratni Devi and wife Nirma Bishnoi have continued his work and are now on a hunger strike demanding protection for khejri trees.

Members of the Bishnoi community during an indefinite hunger strike, demanding a tree protection bill in the ongoing assembly session and a complete ban on cutting of khejri trees, near a Bishnoi Dharamshala, in Bikaner, Rajasthan. (PTI Photo)

Meanwhile, reports of illegal logging in other parts of the state, including in the forest area of Bayana subdivision in Bharatpur district, have further fuelled concerns about enforcement.Activists said the issue concerns the entire desert belt, including Jaisalmer, Barmer, Jodhpur, Pali, Jalore, Phalodi, Sriganganagar, and Churu. Protesters alleged that thousands of khejri trees were felled in recent years, largely for infrastructure and solar power projects.Founder of the Khejri Bachao Andolan, Parasram Bishnoi, said the agitation would continue until the state enacts a specific law making the cutting of khejri trees a punishable offence.“Large tracts of desert land are being indiscriminately handed over to solar parks, destroying the local ecosystem. Without legal protection, the desert’s survival is at stake,” Bishnoi told TOI.He added that participation is swelling daily and asserted that the onus now lies on the state government led by chief minister Bhajan Lal Sharma. Bishnoi alleged that khejri trees were uprooted across vast desert areas both in the name of renewable energy projects and by an illegal wood mafia, with little effective oversight.

Development versus conservation

The unfolding debate reflects a broader tension between renewable energy expansion and environmental safeguards. Rajasthan is a key state in India’s solar mission. Large tracts of land are being allocated for solar parks, transmission corridors and associated infrastructure.

Environmental supporters and members of the Bishnoi community participate in the ‘Save Khejri Movement’ (ANI photo)

While renewable energy is seen as essential for climate mitigation, local communities argue that development planning must take into account ecological realities and traditional land-use patterns. The khejri, embedded in agricultural and grazing systems, is not easily replaceable.For many protesters, the demand is not to halt development but to ensure that it does not erode the ecological foundation of desert life.

An evolving movement

As the Khejri Bachao Andolan entered its sixth day, its trajectory remains uncertain. The state government has indicated it is drafting legislation. Protesters insist on immediate written assurances and a comprehensive statewide ban.What is clear is that the agitation has tapped into a powerful historical memory and a deeply rooted cultural ethos. The khejri tree stands at the intersection of ecology, economy and identity in Rajasthan. Its fate has become a test case for how the state balances development with conservation in one of India’s most fragile landscapes.Whether the movement results in a new conservation law, stricter enforcement or a recalibration of project implementation, it has already reaffirmed the enduring symbolic power of a tree that many in Rajasthan consider their “Kalpavriksha”.